To imagine a language means to imagine a form of life.

—LUDWIG WITTGENSTEIN, PHILOSOPHICAL INVESTIGATIONS

THE GREEN OF MY GRANDMOTHER’S SHIRT

I am writing in a specific setting.

I am writing a specific setting.

I am in a specific scene, while writing it.

The act of writing is part of the scene.

I am writing the scene I am in.

The scene contains elements with and without my writing.

A chair, a piece of clothing, a person, myself.

The house I inhabit is filled with many rooms, and these rooms are filled with many things. One of these rooms is filled with things that for now belong to me.

I am sitting at a table inside the house I inhabit. A shirt once belonging to my grandmother is draped over the chair opposite me.

The frame of the chair is made of dark, polished wood, a gleaming surface that becomes visible to the eye by absorbing specks of light and casting them off again.

The chair is an outlined image, flickering in and out of focus.

As in a broken film, the appearance and disappearance of the image have become one.

The green of my grandmother’s shirt.

A leftover piece of my grandmother’s existence.

What is contained within these threads.

The frame of the chair is dark and sleek. The chair is recognizable.

The chair that has caught in my eye is sleek.

Light glints from its smooth surface, outlining the shape of a chair.

It is the outline of a chair.

The chair is an outline.

It is the outline of a chair, casting shadows.

The green threads of fabric that define itself.

And so you lie there, weightlessly draped over a wooden chair.

You drape yourself over the dark wooden frame.

Do you know of my existence.

You have been touched by many people, many things, in many circumstances. The wooden frame of the chair is dark and polished.

To hold you, is to feel your weightlessness. I have carried you around with me for years.

What do you contain. Where can it be found.

There you are, weightlessly draping yourself over the chair.

A heaviness.

Not confined by the singular threads.

You are contained within threads.

Do you contain yourself within these threads.

Can you be contained.

I have draped you over the back of a chair, a place I would sit and lean against.

A construction allowing people to sit up straight, holding their spines erect. The spine, a complex pathway of nerves connecting a person's mind to all else that makes them.

The back of the chair holding the spine.

The threads holding you.

Person I did not know, who made me.

I feel you with my fingertips.

Brushing against your threads with my fingertips, feeling the singular threads, strumming your strings, I hope to play you.

As my bow connects, the hairs of the horse brushing against the vibrating metal strings, something different is opening up.

The fabric drapes itself.

It is a piece of fabric, of cloth, that drapes itself over the wooden frame.

You are held by a dark wooden frame.

Holding you I can barely feel your weight.

Where are you contained. What do you contain.

THE FIRST OBJECT HE LOOKED UPON, THAT OBJECT HE BECAME

There was a child went forth every day,

And the first object he looked upon and received with wonder or pity or love or dread,

that object he became,

And that object became part of him for the day or a certain part of the day.... or for

many years or stretching cycles of years.

—WALT WHITMAN, “THERE WAS A CHILD WENT FORTH”

I. Angled necks, longer finger boards and added tension in the strings.

Saws, chisels, gouges, knives, plains, files and callipers.

The arching curves of the back and front and the thicknesses of the maple.1

To enter the library of the Rijksmuseum, one must pass through many doors. They are doors of the most different shapes and sizes.

The first door is transparent, and revolving. Four panels, made of glass, are attached to a vertical axis. Similar to the rotation of the Earth, they turn counter-clockwise.

The panels of a revolving door are called wings, or leaves. They must be pushed to open.

And as the air of the outside world is pushed aside, one passes through this cylindrical enclosure and into the sphere of the museum.

One hundred and thirty-one years and thirty thousand square meters. The sphere I have stepped into is circumscribed by these numbers.

One hundred and thirty one, a number incorporated by the Caucasian wingnut tree that has been growing outside, in the museum gardens, since 1885. Cutting horizontally through its trunk, one would see time manifesting itself as a delicate pattern of 131 rings. Examining this pattern, a dendrochronologist is able to read of the most subtle occurences in a tree’s life.

In the shadow of leaves, I stand in the wake of the tree, my hand finds a place to rest on its bark. I close my eyes.

The vibrations of the wooden parts.

Strongly figured maple which glows where the top coating originally wore away.

Light golden-orange to deep red.

I close my eyes, and walk through another door. It is a long slender security gate, made of the Portuguese stone Gascogne Azul. Within the narrow tunnel of the gate, sounds of steps and voices become condensed, and words that are spoken become as hard and smooth as the stone itself. Sounds solidify within the confinement of space, just as they begin to evaporate once it is opened.

Stepping out of the narrow stone tunnel, sound takes on a different tone. It has desolidified. A word that is spoken here extends itself into the museum’s Atrium, covering 2,250 square meters of ground. Within this vast space, sounds become vaporous. The articulation of a word dissolves, and the most carefully strung together sentence falls apart. Mouths move, yet it is difficult for the ear to catch the words they are forming. Sound is a fine shape shifter, adapting itself to the space it is contained by. Here, it has become as light and airy as the Atrium itself.

Beautifully transparent.

The Atrium is referred to as the heart of the museum by its architects, Cruz y Ortiz. It was constructed in the course of the Rijksmuseum renovation, a project undertaken in the years 2003 to 2013, and functions as an entrance square.

Standing in the heart of the museum, I listen to its sound.

The sound I hear is a hum, in which singular words are ungraspable, one voice indiscernable from the other. All threads of sound are interwoven. They have merged together into one large sound tapestry that covers the whole of this vast interior space. The hum is the sound of the space itself.

I stand there, listening to the space. Its hum fills my ears, and after a while, it has filled my entire body. The space is inside of me, as I am inside of it.

The streets themselves, and the facades of houses... the goods in the windows,

Vehicles... teams... the tiered wharves, and the huge crossing at the ferries;

The village on the highland seen from afar at sunset...the river between,

Shadows... aureola and mist...light falling on roofs and gables of white or brown,

three miles off,

The schooner near by sleepily dropping down the tide... the little boat slacktowed

astern,

The hurrying tumbling waves and quickbroken crests and slapping;

The strata of colored clouds...the long bar of maroontint away solitary by itself...

the spread of purity lies motionless in,

The horizon’s edge, the flying seacrow, the fragrance of saltmarsh and shoremud;

These became part of that child who went forth every day, and who now goes

and will always go forth every day,

And these become of him or her that persues them now.

—Walt Whitman

II. Angled necks... The vibrations of the wooden parts... Beautifully transparent...

The catalog of the Stradivarius exhibition is part of the collection of the Rijksmuseum library. Sitting in the library to view the catalog, I am encircled by 5.4 kilometers of books, sixty thousand volumes, filling shelf after shelf, spiraling up along the mezzanines, reaching far up to the glass ceiling, where a kinetic sculpture by Alexander Calder gives the impression of gliding.

Antonio Stradivari (1644-1737) created an estimated 1,160 instruments, nine hundred and sixty of which were violins, six hundred and fifty of which survive today. Twenty-one of his instruments were featured in the exhibition.

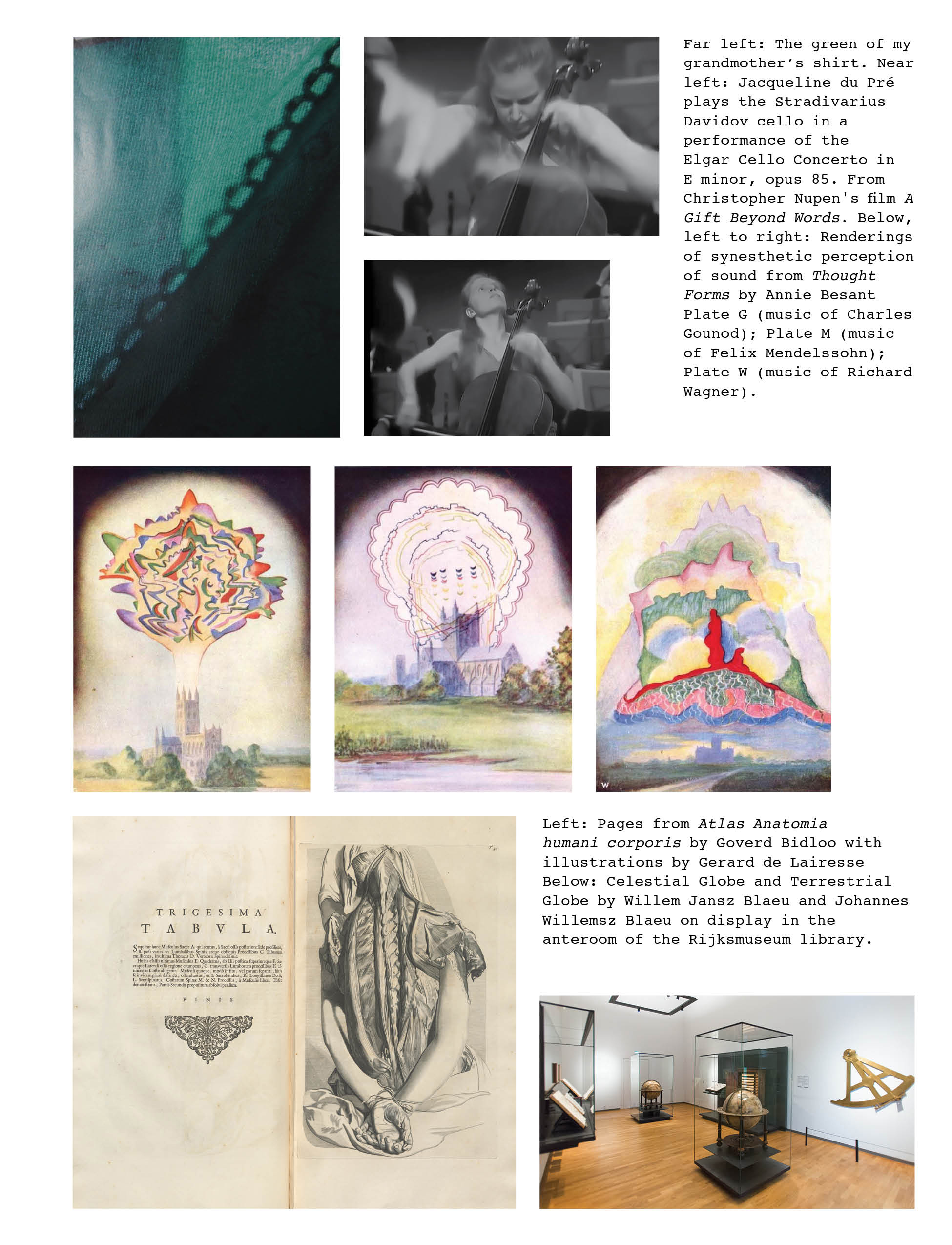

Stradivari's instruments are recognized as among the finest bowed instruments created. At present, the cost of one lies at several million. They are in the hands of virtuosi such as Yo-Yo Ma, who plays the Davidoff Stradivarius, a cello of 1712, an instrument previously played by Jacqueline du Pré.

In her years of playing it (1964–1970), du Pré had commented on the instrument’s unpredictability, to which Yo-Yo Ma later replied, that her “unbridled dark qualities went against the Davidoff. You have to coax the instrument. The more you attack it, the less it returns.” The instrument was passed on to Yo-Yo Ma after Jacqueline du Pré’s death in 1987 and has been played by him ever since.

The Soil Stradivarius of 1714, regarded as one of the finest violins made during Stradivari’s golden period, is played, at present, by violinist Itzhak Perlman.

“The Stradivari violin has been much imitated but never bettered as a robust, responsive and expressive instrument,” writes Dr. Jon Whiteley, curator of the Stradivarius exhibition.

Furthermore he states, “A fine violin depends on a combination of good materials and fine craftsmanship. There are no significant mysteries in a Stradivari violin and no single answer explains its superiority. The close-grained, resonant pine from the nearby Tyrol used for the fronts of his instruments was shared by his colleagues and his oil varnish was a variant of the common Cremonese type.”

Objectively speaking, the unknown element giving Stradivari’s instruments their remarkable expressiveness and responsiveness is not to be found. In its materially graspable components, a Stradivarius does not differ from the many other violins made in Cremona at the beginning of the eighteenth century.

Perhaps the unknown element can be located, yet not grasped. It may be an immaterial quality, a component to be found, or understood, through sensuality, rather than materiality. As is sensed by the musicians who have played it, the instrument has a character of its own.

1967, Wood Lane studios—before an invited audience, du Pré performs the Elgar Cello Concerto in E Minor, op. 85. second movement (lento—allegro molto). Minute 1:23, her fingers leave the neck of the cello, to brush over her face, from nose to cheekbone, a touch that is silent, becomes a touch that is heard, in minute 1:25, as her fingers return to the cello.

The instrument releases a sound communicating something besides the simple physicality of fingers pressing down on strings. It is a meeting of flesh and metal, wherein the musician's touch seems sensual, rather than technical, wherein the instrument seems to exert a vast capacity to receive, absorbing every hue of forcefulness and subtlety that lie within the musician’s impulses and transmuting all into sound, giving back to the musician, and the one who listens, all that has been put into it. A cycle is created, in which a certain dialogue takes place, a movement between and in between subject and object.

It is as though Stradivarius has created bodies of sound, uniting within them two elements that may be described as dualing, these being sensitivity and strength, or as attributed by Whiteley, robustness and responsiveness. It may be that it is within the incorporation of this duality that the body of the instrument is able to withstand the force and fullness of a musicians touch, while at the same time remaining permeable to it.

Minute 1:23 to 1:25, three seconds caught on film by Christopher Nupen, an outtake from the documentary Jacqueline du Pré and the Elgar Cello Concerto (1989).

This film begins with an account of her activities after the onset of her illness. It ends, at Jacqueline du Pré’s request, with a re-edited version of the film which we made with her in 1967, a film which sketches her childhood and the development of her musical talent, her meeting with Daniel Barenboim and their marriage in 1967, her relationship with the Elgar Concerto and, finally, a complete performance of the work with the New Philharmonia Orchestra conducted by Daniel Barenboim—a performance that is remarkable by any standards and, for many, quite unforgettable.

—Christopher Nupen

Jacqueline du Pré was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis in 1973, after she had begun to loose sensitivity in her fingers and other parts of her body. The onset of the illness led to an irreversible decline in her ability to play the cello. Having lost the sensation in her fingers, she had to coordinate her fingers visually. Her last London concerts were in February 1973, including the Elgar Concerto with Zubin Mehta and the New Philharmonia Orchestra. She died in 1987, at the age of forty-two.

She had a capacity that was very rare—she could become one with the music.

—Daniel Barenboim

It is as though, being in the hands of one who is attuned to the body of sound, who is equally able to withstand and at the same time be permeated by the sound that has been inforced by him or her on the instrument, an exchange takes place between musician and instrument, and the meeting between subject and object takes on a life of its own, manifesting itself in the world as a wonderous expression of sound.

Playing lifts you out of yourself into a delirious place.

—Jacqueline du Pré

WHEN OBJECTS ARE LOST, SUBJECTS ARE FOUND

I. When objects are lost, subjects are found.

—SHERRY TUCKLE, EVOCATIVE OBJECTS: THINGS WE THINK WITH

Plates G., M., and W. are renderings of a synesthetic perception of sound. The music of three different composers, Gounod, Mendelssohn, and Wagner, has been associated with color and form, creating three different shapes, that tower above their place of performance, the cathedral.

These depictions appear in the book Thought Forms by Annie Besant published in London in 1901.

In the chapter “Forms Built by Music,” she defines these synesthetically perceived shapes as thought forms, writing of them as “the result of the thought of the composer expressed by means of the skill of the musician through his instrument.”

Entering the anteroom of the Rijksmuseum’s library, it is a place that seems to be filled with thoughts.

They are thoughts that stand still.

They are thoughts that have been formed into objects.

They are thoughts that have become detached from the time and place they were thought in.

They are thoughts that have outlived the thinker.

Celestial globe

Willem Jansz Blaeu (1571–1638),

Johannes Willemsz Blaeu (1596–1673)

oak, papier-mâché, copper, metal, hand-coloured engravings,

1645–1648

In 1633 Willem Jansz Blaeu was appointed official mapmaker of the Dutch East India Company (voc). In order to chart the stars, helmsmen were asked to record the positions of the heavenly bodies. The names of some of the constellations—such as Boötes, the giant chasing of the Great Bear on the globe—are no longer familiar.

A thought of space has been caught within the form of a globe.

My breath against the cubical glass vitrine it is held in, leaves a small clouded shape. The Celestial Globe is mirrored by its twin, the Terrestrial Globe.

Both objects have been placed along the central axis of the anteroom. Daylight does not reach here. In the darkened room, the hand-colored engravings of continents and constellations appear as shadows, drifting over the sphere’s reflective surface, in gradual decay.

The plaque on the wall of the anteroom, describing the Terrestrial Globe, speaks of an incorporation.

This globe was made in the workshop of Blaeu senior and junior in Amsterdam. These cartographic publishers kept abreast of the latest geographic discoveries, which they incorporated in their globes. This showpiece has a diameter of 68 centimetres. It includes “Nieu Nederland” (New York), the colony founded in 1625, as well as the then only partially known coast of “Hollandia Nova” (Australia).

Thinkers, cartographic publishers, have incorporated thoughts, geographic discoveries, into objects, globes. An object has incorporated a thought, a discovery. A thought has been transferred into a space outside of the thinker. A space has been formed from a thought of space. The shape of my breath against the glass vitrine has already faded away.

In the theory of Annie Besant, thoughts may take form in several different ways:

From the point of view of the forms which they produce we may group thought into three classes:

- That which takes the image of the thinker....

- That which takes the image of some material object...

- That which takes a form entirely its own, expressing its inherent qualities in the matter which it draws round it…

We have often heard it said that thoughts are things, and there are many among us who are persuaded of the truth of this statement. Yet very few of us have any clear idea as to what kind of thing a thought is, and the object of this little book is to help us to conceive this.

Although determining thoughts as “things,” thought forms remain largely ethereal in the scope of the book. In most instances, they appear as invisible entities, visually perceivable only “to those who have eyes to see,” such as the synesthetically perceivable “Forms Built by Music.”

As she recounts, however, the experiments of French physician Hippolyte Baraduc (1850–1902), Besant acknowledges that thoughts may manifest themselves in a material sense:

Dr Baraduc obtained various impressions by strongly thinking of an object, the effect produced by the thought-form appearing on a sensitive plate; thus he tried to project a portrait of a lady (then dead) whom he had known, and produced an impression due to his thought of a drawing he had made of her on her deathbed.

He quite rightly says that the creation of an object is the passing out of an image from the mind and its subsequent materialisation, and he seeks the chemical effect caused on silver salts by this thought- created picture.

In the chapter “The Form and its Effect,” she writes of thought forms that are bound to neither subject nor object:

If the thought-form be neither definitely personal nor specially aimed at someone else, it simply floats detached in the atmosphere, all the time radiating vibrations similar to those originally sent forth by its creator. If it does not come into contact with any other mental body, this radiation gradually exhausts its store of energy, and in that case the form falls to pieces; but if it succeeds in awakening sympathetic vibration in any mental body near at hand, an attraction is set up, and the thought-form is usually absorbed by that mental body.

Besant positions her investigation just outside of, yet still touching, the border of science: “Röntgen’s rays have rearranged some of the older ideas of matter, while radium has revolutionised them, and is leading science beyond the borderland of ether into the astral world. The boundaries between animate and inanimate matter are broken down.”

- Ebony, veneered with tortoiseshell, velvet, brass. An object has taken on the form of a thought of time. Coster clock, with a pendulum movement, invented by Christiaan Huygens, c. 1659.

Back and forth, the pendulum swings, an oscillatory movement, occuring for instance in the beating of the heart, the vibrating strings of musical instruments, or in the swelling of Cepheid variable stars.

In the anteroom, the pendulum clock stands still.

The timepiece is on display behind glass, standing in the midst of other still objects. To its right lies Anatomia humani corporis, the first atlas to show illustrations of the microscopic anatomy of the brains, skin, liver, and stomach, conceived by Govard Bidloo and Gerard de Lairesse, Amsterdam, 1685.

The atlas has been opened to a page exhibiting an illustration of a human corpse, dissected to reveal the spine, a cut onto the base of the head, where the spinal cord connects to the brain.

Man, the Thinker, is clothed in a body composed of innumerable combinations of the subtle matter of the mental plane, this body being more or less refined in its constituents and organised more or less fully for its functions, according to the stage of intellectual development at which the man himself has arrived.... Every thought gives rise to a set of correlated vibrations in the matter of this body. The body under this impulse throws off a vibrating portion of itself, shaped by the nature of the vibrations—as figures are made by sand on a disk vibrating to a musical note. We have then a thought-form pure and simple, and it is a living entity of intense activity animated by the one idea that generated it.

—Annie Besant

The body of the pendulum clock has been unlocked and opened, the key placed directly beside it. The inside of the clock reveals multiple layers of inner mechanical workings. Its layers appear as thick, metal pages, with sentences made of tiny golden wheels. They function as the timekeeping element of the clock, a mechanism translating time into a sequence of movements. The back and forth movement of the pendulum is translated into rotational movements, drawn by the hands of the clock. On the face of the clock, the hands draw circles as they crawl along the units of seconds, minutes, and hours. Time has been cut into pieces, dissected, and locked into the body of a clock. It is within this invented mechanism, or thought form, that time appears to be passing, and moving forward, repetitively.

Eight objects, on display in the anteroom of the Rijksmuseum library, positioned next to the pendulum clock.

In the foreground, six medals:

Comets were considered such an extraordinary natural phenomenon that medals were specially struck to commemorate them. Often people did not understand what they were.

On the right, a golden, oval form:

Pocket noctural and astrolabe of René Descartes, France, c. 1600–1650, gold, silver

This instrument was made especially for René Descartes (1596–1650). The Frenchman resided in the Dutch Republic from 1629 to 1650, during which time he conducted experiments and wrote his most important philosophical works. He could use this convenient pocket instrument on his travels. To determine the time at night, the nocturnal (or nocturlabe) had to be aligned with the Pole Star. It also houses a sundial and a compass.

In the background, a tile:

A father and son stand side by side, the ground beneath their feet a fast brushstroke of blue, their hands reach out toward the sky, palms facing upward, in praise of the comet that passes above, slow and sweeping and blue is its tail, paint on a tile, commemorating a moment, 1664 reads the inscription, painted in blue at the end of the fast brushstroke, at the beginning of which stand father and son.

A rippled oblong mass is projected by three persons thinking of their unity in affection. A young boy sorrowing over and caressing a dead bird is surrounded by a flood of curved interwoven threads of emotional disturbance. A strong vortex is formed by a feeling of deep sadness.

—Annie Besant, on Dr. Baraduc's thought-created pictures

IN ONE ROOM, THE SCENT OF A BOOK

The green of my grandmother’s shirt.

What do you contain. Where can it be found.

Cut open the back of a chair, a place I would sit and lean against, a place of dissection and thought forms.

A dark wooden frame. Weightless.

Can you be contained.

In one room, the cover of a book.

In one room, the scent of a book.

In one room, the act of writing itself.

Where are you contained. What do you contain.

Fingertips and shadows, mist and metal strings.

In the shadow of leaves of a wingnut tree, in the revolving leaves of a door, and in the Leaves of Grass of Walt Whitman.

From nose to cheekbone, a delirious place.

A strand of hair, from a bow.

Small shapes of breath, glass, and a feeling of deep sadness.

—DEDICATED TO MY GRANDMOTHER

INGEBORG MARIA MIKUTTA (1936-1967)

1. All italicized passages in parts I & II of this chapter are excerpts from the catalog for the exhibition Stradivarius at the Ashmolean Museum of Art and Archaeology.